Darkness blanketed almost everything before us, save for the incandescence of an electric bulb escaping through the gaps of shut windows from the house on our far left. In its compound stood an imposing tree, its immense trunk and thick foliage was veiled in a shroud of black. Even in daytime, it always invoked a sense of unease in me. Towards our right, a fence of rusty zinc sheets hammered together towered over us.

The trail wound its way around houses built haphazardly. Construction debris, sand and gravel were dumped discriminatingly to fill up indents in the ground and also to prevent puddles from forming during the rainy seasons. It was the same narrow scraggy trail my mother had traversed many times every day. This time, it was different, though. There was urgency in her steps.

A few paces ahead, our next door neighbour led the way with a torch light in hand. She was a few years old than my mother. I was later taught to address her as tua ee, eldest aunt in the Chinese Hokkien dialect, although we were not related in any way. My mother and tua ee spoke little along the way. When they did, it was in hushed tones.

I could feel the thumping of my mother’s heart as I rested on her shoulder. Even in the coolness of the night breeze, her blouse was damp with perspiration. I was too exhausted to be bothered, my energy sapped by numerous episodes of diarrhea and vomiting earlier in the day.

From the narrow trail, we emerged into a wide open space and a crossroad. Before us, it sloped down towards Jalan Balik Pulau. The houses on both sides of the incline were mostly unlit. A solitary street lamp illuminated the road in the distance. My mother and tua ee made their way down one careful step after another. Certain parts of the trail were steep and slippery. A wrong footing could send all of us tumbling down.

Just as we were crossing the road at the foot of the slope, the whirring sound of an approaching vehicle broke the silence of the night. My mother and tua ee quickly ran and hid behind some cars that were parked nearby. They both crouched there, listening intently to the roar of the engine that grew louder and louder.

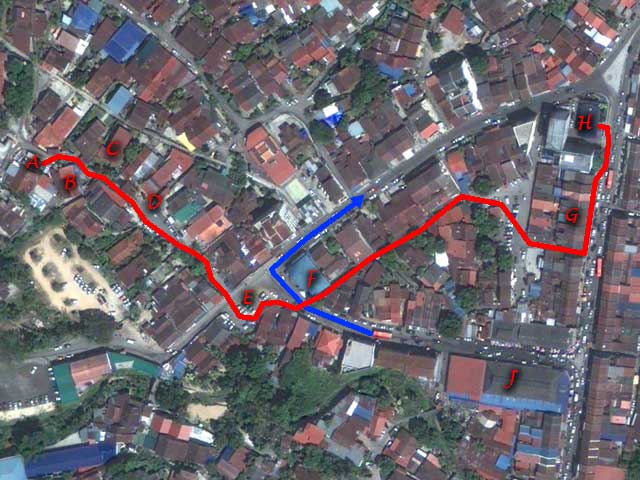

Google Earth image of Ayer Itam town and the route my mother and tua ee

took during the 1967 Penang Hartal.

Legend:

Red – route that my mother and tua ee took

Blue – route of the lorry

A – the house we stayed in

B – the house tua ee lived in

C – the house with the big tree

D – open space and crossroad

E – car park where my mother and tua ee hid from the approaching lorry

F – Beng Chim Garden kopitiam

G – block of shophouses opposite the Ayer Itam bus terminal

H – Ayer Itam police station

J – Ayer Itam wet market

I peeked out from between cars and saw the headlights of a lorry as it passed by. My mother shushed me. The lorry turned the corner and disappeared down the road. It all became eerily silent again. Except for the illumination of street lamps, there was no sign of life in the entire town of Ayer Itam.

When all was clear, my mother and tua ee quickly crossed the road and ducked into a side lane between a kopitiam and a tailoring shop. Walking as fast as their legs could carry them, and me, they appeared at the other side of town opposite the bus terminal.

The shadows in the five foot way provided some cover for the short distance to the balai (police station). The policemen were surprised to see us. He scolded my mother and tua ee for breaking curfew and said that we could have been shot if we were caught en route. My mother explained that I was ill and needed to go to the hospital. The policeman made a phone call and then asked us to wait.

When a police jeep arrived, we were ushered into the back. Two policemen climbed in to accompany us. There were road blocks along the way. We were stopped several times. The people manning the checkpoints would shine their torches at our faces and then waved the vehicle on.

I remember my mother carrying me down from the back of the jeep at the main entrance of the Penang General Hospital. I still remember the dimly lit corridors and the wooden benches. I also remember the nauseating odour. I remember the nurses moving about in the darkness. My mother held me in her arms the entire night after I was treated. The next moring, after curfew was lifted, my father, who was away the night before, came to pick us up.

Three decades later, I asked my mother about that incident. All the while, I thought that it was the curfew during the May 13 riots in 1969. She could still remember clearly the harrowing experience that she and tua ee went through that fateful night. According to her, it was during the currency and coin riots. She did not elaborate about the causes and consequences of the events though. I had no idea when that happened and what transpired until recently when I read about the Penang Hartal of 1967.

In November 24 of that year, following the devaluation of the Malayan currency a few days earlier, businesses were closed as a sign of protest. It turned violent and racial when the different ethnic communties clashed and lives were lost. Curfew was imposed in Penang island and several districts in the mainland. Malay and Iban soldiers were sent to quell the violence.

I was just fifteen months old in November 1967. Although my memory of those times are sparse, every now and then, I would have occasional flashbacks of that night, like hiding behind the cars, the time in the balai and the dark corridors of the Penang General Hospital.

The toddler in me then could not comprehend the danger that my mother and tua ee put themselves through. As I reflect back now, I am thankful that my mother and tua ee risked their lives to seek medical attention for me. Thank you! They have both passed on. There is no way for me to express my gratitude except to share the story of their courage here.